Social media services such as Facebook, Instagram, X, and TikTok are about to get a bit of a shake-up. Come December, the Australian government will be placing restrictions on its younger citizens from access social media in a move largely heralded as a world first.

Commonly known as “the social media under 16s ban”, the Social Media Minimum Age Bill amending the Online Safety Act 2021 will aim to use age assurance technology to ensure people under the age of 16 can’t easily and readily access social media, while still allowing people over the age of 16 to not get caught in the crossfire.

YouTube was added recently, as well, so while typical social media services are the target, the mere act of watching videos could see age verification expand to everyone in Australia.

While the government rushed through the time for the population to respond to its plans, and still pushed on all the same, an Age Assurance technology trial has been running for several months, testing to find out whether age analysis can work for social media.

A few hundred pages of testing approaches, methodologies, and results have been released as part of the government’s Age Assurance Technology Trial Report, and while it makes for riveting reading, the results are there: age assurance technology can work, but it may be prone to errors.

Over 60 solutions were evaluated from 48 providers, and while some appear to work, age verification is not without its flaws.

They include incorrect age guesses both for those under 16 and beyond it, while errors may be more problematic for women than men, and potentially with variations in skin tones. Some kids will be prevented access, and others won’t, at the same time when some adults may lose access in the process.

And that’s without looking into how long it could take for some users to get into the service. In some instances, an age check would take anywhere between 10 minutes and an hour, though on average would take under a minute before the system has identified whether or not the person’s age has been correctly guessed.

Going by the data, there are clear problems, but what also stands out about the report?

Testing skipped over two of Australia’s biggest cities: Sydney and Melbourne

One of the methodologies that strikes this journalist as a little odd is where the testing was run, or rather, where it wasn’t.

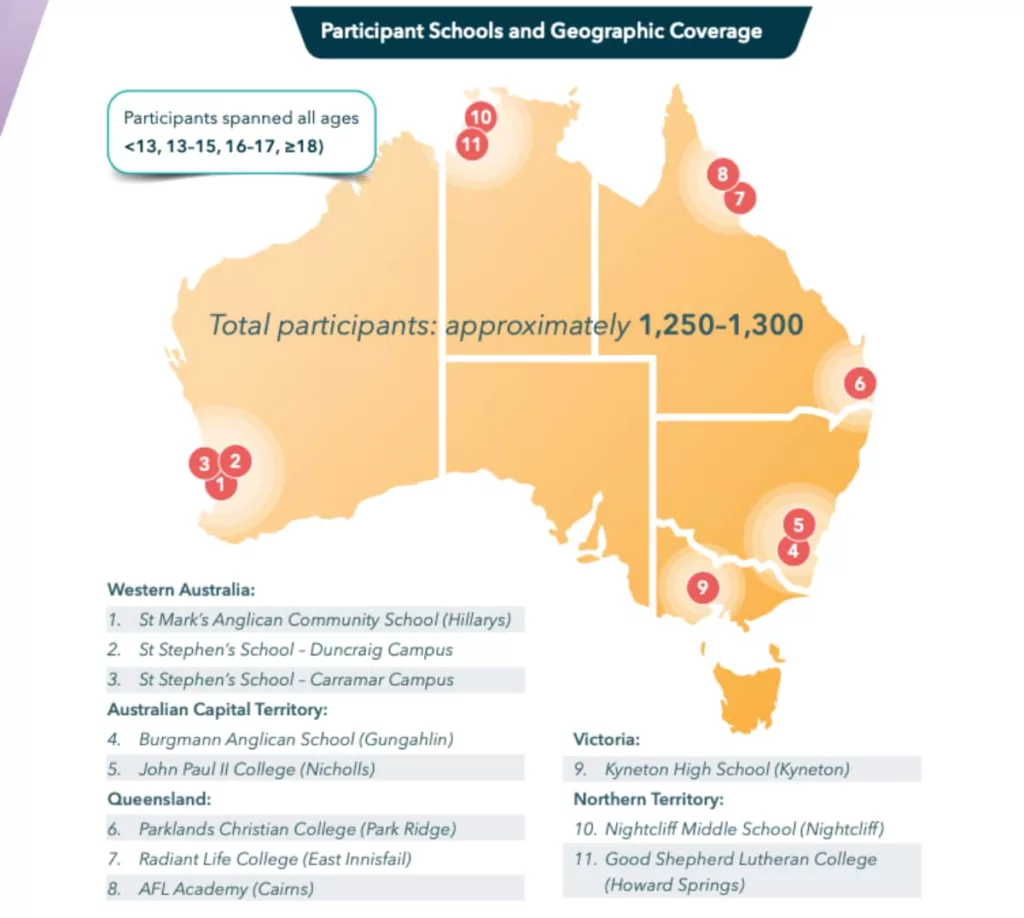

Specifically, the participant schools covered most of the country’s states, but not the two biggest cities in the country: Sydney and Melbourne. Neither city saw a school, and out of the two states each is from, only Victoria nabbed a testing school.

There’s no reason to suggest students in schools outside of the major cities would be better subjects for a nationwide age assurance system, and we’re certainly not making any inferences or assumptions, but it does make a valid question: why were NSW schools not included on a nationwide trial, and what was the reason for that methodology?

False positives for the underage

A combination of technologies may eventually be used to work out whether a user is young or of age, but there are some catches.

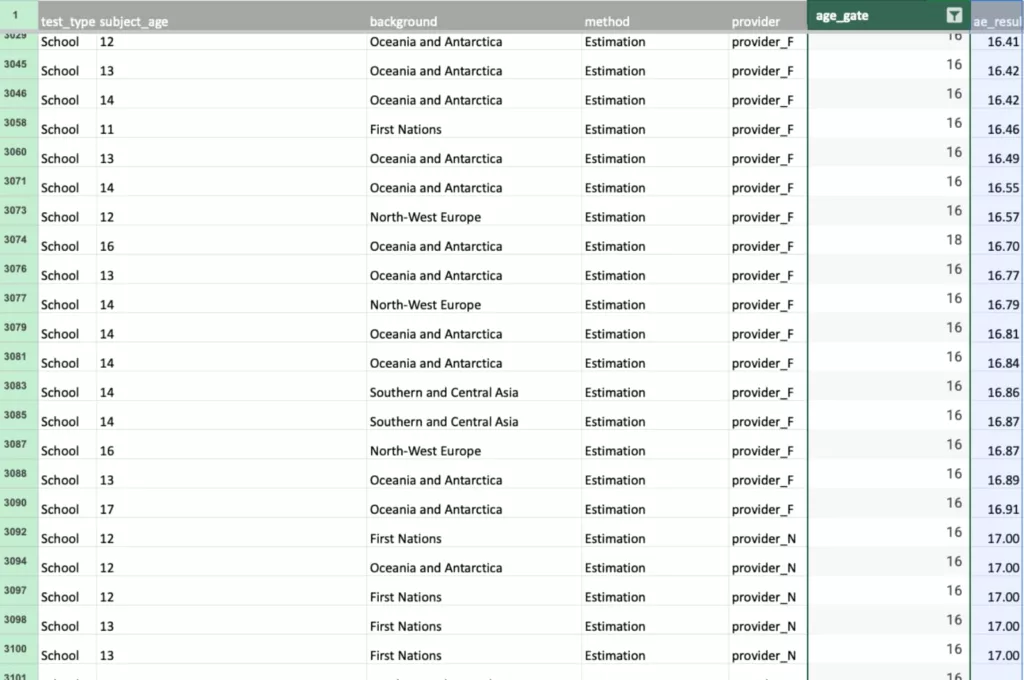

For instance, the age gate managed to pick up on false positives, though tracked to fewer the older the person was. A child tested for an age gate of 13 and older could trigger false positives for age 16, but could also trigger for below, aged between 11 and 12.

However, the system also notes that false negatives occurred for 16 and 18 year old being misclassified for those between 12 and 13 for the former and between 13 and 14 for the latter, suggesting uncertainty will still be an issue for some in certain groups.

The long and short is that while the system will never be perfect, some kids will likely be able to evade the technology, while some adults may struggle to get into their accounts.

Parental control and consent systems weren’t tested

Interestingly, while the government report notes that parental control and consent may be effective, it didn’t actually try either as part of its approaches in the reports.

Instead, the tests for parental consent being used as a means was a lab-based simulation (Part H, page 18), and no verification of parental identity was tested. There are valid reasons for this, such as interfering with approaches used by actual families, but the report does not that “children’s participation in the consent process was not directly observed” and “no behavioural testing was performed”.

To put it simply, the report says clearly:

“The evaluation did not explore how children or parents interact with consent prompts under real conditions – including issues of digital literacy, comprehension or power dynamics in decision-making.”

That does seem like something that would matter, especially as the report found parental consent mechanisms existed, and while they don’t technically establish age, they “instead provide a formal pathway for adult approval where such access is required”.

Age checking could just crash

In some instances, the system just stopped working, the report noting that on page 22 of Part C.

No volume stress testing was performed, a factor which matters when it’s going to come into play for millions of Australians faces with using this platform. Even without the stress testing, the system failing is clearly an issue.

An age check process might just not work, and you’ll have no idea why.

Social media organisations may need to be more responsive

One aspect of the trial’s report doesn’t seem like it would connect with social media management at all, particularly if you have a problem.

If you do end up having a problem with social media, such as if your account is compromised and you need to talk to the powers that be running the platform. That’s a problem simply because they might not get back to you in a timely way, if ever at all.

Even journalists can get incorrectly grouped and have their access removed, a problem this writer has published at the AFR before.

So imagine the problem if an age assurance system incorrectly declares your age and locks you out. Not only do you have no access, but you’ll need to talk to the social media’s support team to get it sorted.

That’s something the report cites, noting that “to achieve high acceptability, systems would need to be:

- Understandable

- Fair

- Reversible when wrong; and

- Designed to respect user autonomy and privacy”

Most of these seem possible, but social media’s tendency to take days to weeks to simply have a decision changed or revoked definitely suggests the logic of “reversible when wrong” probably wouldn’t happen.

Where do you stand?

We’ve heard since the beginning of this ban that not only is it not a ban (even though it is), that parents will be able to decide whether it’s enforced or otherwise.

Essentially (from what we understand), it won’t be a crime if parents decide to ignore the social media age ban and bypass it for their children. Whether social media entities will allow it is another question altogether.

But it does seem like everyone will be faced with a variation of these technologies regardless when the government rolls it out by December. That is potentially a problem.

If anything, it does appear that much like the government’s insistence of hurrying the response to the ban, the trial has all the makings of a rushed exercise, and could need more time in the kitchen.

And that’s all before you find out whether a social media entity decides to remain in Australia because of its now-forced commitment to adhere to the new rules. Smaller services such as Bluesky may struggle with that request, while larger entities such as Facebook and X have the funds to implement the changes and keep their customers and users around.

It means that when the new social media age assurance requirements do roll out, the government’s solution may not be the bulletproof solution some parents expect it to be, and may need to be married to parental control and consent to actually be properly effective.