The eSafety Commissioner wants YouTube included as part of the age ban set to apply for other social media services. There’s some logic to it, but it also has the potential to do harm.

Australia is still on track for a social media ban, and it appears one of the world’s biggest video websites is in the crosshairs.

What was originally a set of draft rules and age verification technology designed to prevent kids under the age of 16 from being pulled into a murky world of social media has changed, largely because the definition of social media has changed over time.

It’s easy to look at social media and see Facebook, X, Bluesky, and Instagram, as they’re all services designed to share information. That is the very definition of social media: media to be social, and media to be shared.

The problem is that this definition technically covers lots of other media, as well.

TikTok is a social media platform built on sharing video, as is Snapchat. And if they’re all fair game, so technically is YouTube, what is arguably the world’s biggest video sharing platform.

YouTube videos don’t have to be shared socially in the same way that a TikTok or Snapchat video would — they’re both app-based systems where the videos exist inside their social media ecosphere. But YouTube is definitely similar, because it has an app and a website, making it both a video platform and a social platform, significantly muddying the waters some.

YouTube has legitimate uses for under 16s

It’s easy to group a harmful product with another harmful product when viewed from the lens of “both are created to cause harm”. Social media and online video services aren’t quite as black and white.

While much of the media on YouTube isn’t meant to be consumed by those under a certain age group, a lot of it is, and some of it is used for education. School curriculum programs used by schools as early as Kindergarten in Australia rely on YouTube, while kids also use YouTube for science, art, and music lessons.

You can learn from YouTube. You can be entertained by YouTube. You can listen to music on YouTube.

Simply put, a lot of what can be found on YouTube as well as on other streaming services can be perfectly find for kids and teens, and an outright ban preventing access could do more harm than good.

There are clear risks

However, there is also danger.

Policing the internet is next to impossible, and so while perusing YouTube is very different from perusing YouTube Kids, both can have videos slip through the cracks. Worse, kids can go looking and find something potentially harmful.

“We surveyed more than 2,600 children aged 10 to 15 to understand the types of online harms they face and where these experiences are happening,” said Julie Inman Grant, eSafety Commissioner for Australia, at the National Press Club this week.

“Unsurprisingly, social media use in this age group is nearly ubiquitous – with 96% of children reported having used at least one social media platform.”

“Alarmingly, around 7 in 10 kids said they had encountered content associated with harm, including exposure to misogynistic or hateful material, dangerous online challenges, violent fight videos, and content promoting disordered eating,” she said.

“Children told us that 75% of this content was most recently encountered on social media. YouTube was the most frequently cited platform, with almost 4 in 10 children reporting exposure to content associated with harm there.”

As one of the largest media sites in the world, having YouTube turn up as “the most frequently cited problem” probably won’t come as much of a surprise. That doesn’t drive down its importance, but it can change the expectations slightly. YouTube has been around for 20 years this year, hosts nearly 15 billion videos, and has over two billion users.

YouTube is the biggest video platform out of the lot, and probably would be the most cited video platform in any survey or research.

A parental solution

I’m sure I’m not the only person to have said this, but bans rarely work. If anything, they turn the rule into a challenge, and essentially ask the group affected most by it to find ways to circumvent it.

As it is, while the eSafety Commissioner has said the social media regulations aren’t a ban, they will be construed as such, something that’s a clear problem.

Also a problem is the technology underlying the issue, which has already seen one expert resign from its advisory board. That’s not a great start. There isn’t a lot of information as to how age checking technologies would work with the approach, which would likely put the burden on the providers to ensure it’s followed.

Blocking ages was always going to be a problematic issue. Artificial intelligence could end up helping, or it could end up being overly aggressive and not working at all.

Ultimately, parents should be where this issue goes back to. If a parent has their own social media account — be it on YouTube or Facebook or Instagram or wherever — the account could theoretically be tied to the parent’s account, where the rules will be controlled.

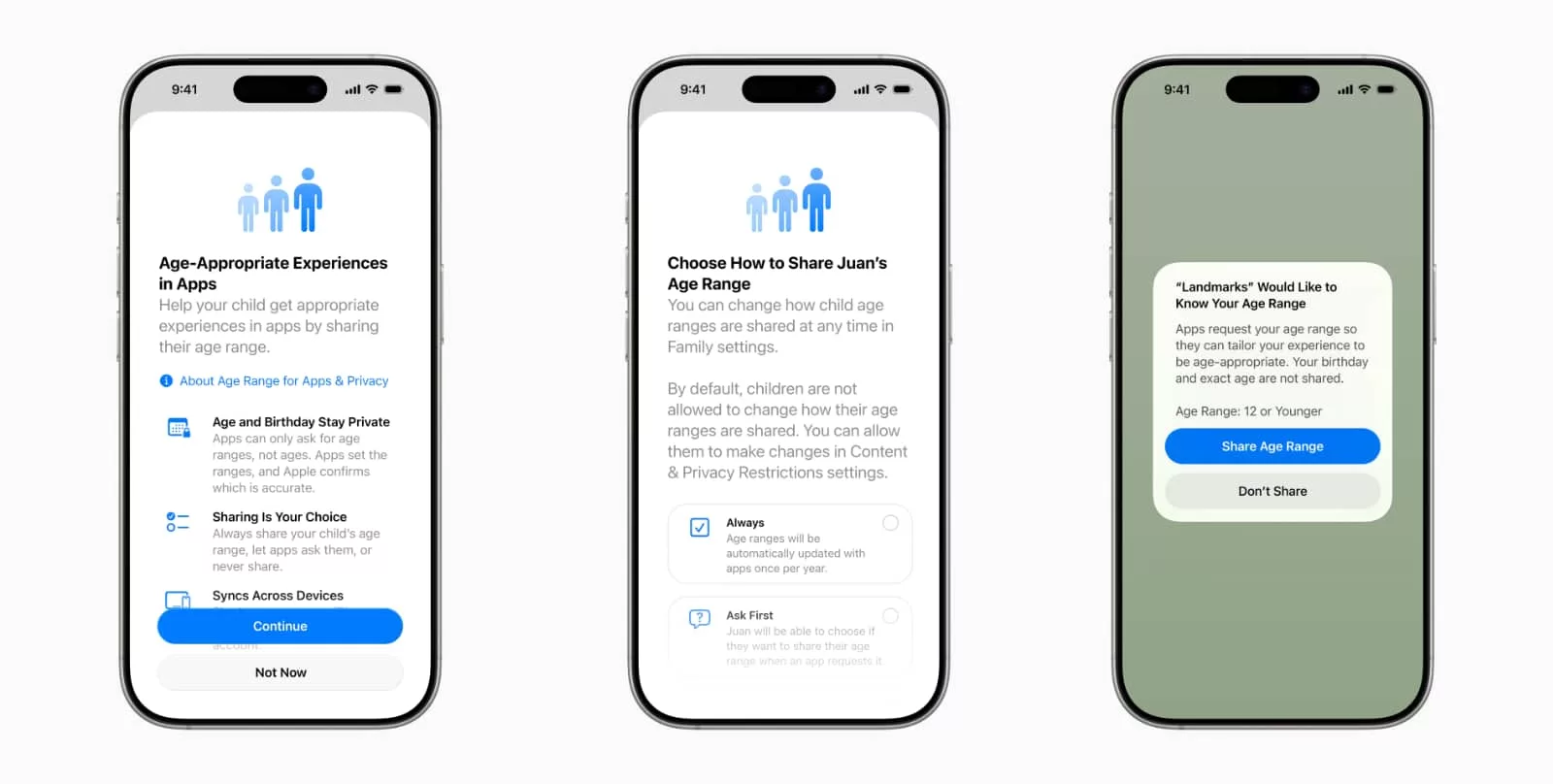

It’s not dramatically dissimilar from how Apple or Google do things when it comes to setting up a child’s phone or tablet, and there are greater controls coming later in the year.

Social media players have also largely been working towards the idea, with Instagram providing locking controls for teen accounts, while TikTok recently added its own approach to the idea. Bringing parents back into the fold means they get to become aware of what their kids are doing and watching, and being the parents throughout.

And yes, before anyone asks, it is technically impossible to run a fine-tooth comb over the internet and keep an eye on every video your kids and teens watch.

However, as someone who is building an AI system can tell you, social media platforms can use their assortment of AI tools to analyse videos, work out intent, and quickly work out whether a video should be shown to a certain age group.

If I can work out intent with question and answer pairs from an article, then Google can use its own aptly named “Video AI” Cloud Video Intelligence API platform to do the same with videos on its own platform. This probably isn’t rocket science.

While I am not a moderator on YouTube, it doesn’t take much to see YouTube could adopt a policy where logging in shows a set of videos distinctly different to being logged out. As it is, YouTube is a platform that doesn’t require you to be logged in to watch anything, making embedded videos possible.

If more analysis was performed preventing videos from reaching a certain audience, it would be a step in the right direction to limiting problematic content.

Education is still an answer

You can’t prevent everything, though, and so that’s why we have another perfectly incredible tool at our disposal: education.

Education gives us — parents and students and educators and scientists and politicians and adults and kids of all kinds — the ability to learn and work collectively, collaboratively, using our best sense to work out what to do and what not to do.

As a parent, I can teach my kids that it’s fine to come to me to talk about what they see, and I can also explain to them how to use social media. I can teach my kids how to be good netizens.

Importantly, I can talk them through the internet, and I can use the assortment of parental controls to limit what clearly shouldn’t be accessed at an early age as they grow.

Social media providers are now being forced to do more, which can only be a good thing, but it’s also only the beginning.

The ban also likely wouldn’t be enforced

The other critical problem extends from what the government noted last year when the social media ban popped up as a concept: the ban wouldn’t be entirely enforced.

That is to say companies would have to follow the rules designated by the government, and prevent sign up from kids under a certain age group, but parents could technically override it if they choose to. There would be no penalties if a parent circumvented the rules and ran afoul of the Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Bill 2024, which would amend the Online Safety Act 2021.

An unenforceable bill doesn’t have a tremendous amount of power, and the government’s lack of time to argue for and against the bill last year really suggested that like many things in government, there wasn’t really much of a plan, either.

Like many others, we provided a submission response in the one day the government gave bodies a chance to argue a case (announced on November 21, closed for submission on November 22). From what we can surmise, most weren’t read out when it came time to discuss the policy with the governmental panel.

It’s frustrating to note that the government gave so little thought to allow a proper response, a move that seemed designed to prevent any real thought from going in or conversation about the move, which it appeared planned to act on regardless.

Worse, while the government has said the age assurance technology can work, it has yet to provide any details of the tests it conducted to prove that. Despite this, the date for later this year remains on the cards despite any proof, with December likely to see the rules go into effect.

Unfortunately for parents, the ban and its approach remain an idea that desperately needs consultation and details to deliver an approach that can work for all. We’re not sure we’re there yet, and the government clearly needs to explore more options before committing itself to the December rollout.