Running a website isn’t easy, but running one that gets hacked, or looks like it has? More frustrating. What’s worse is when Google turns that into something for others to see, read, and believe.

And if it’s misinformation purporting to be in the name of your business? Potentially worse.

A recent story jumped out at me as I was doing the regular rounds and reading the excellent work other journalists in the industry: Google had a problem.

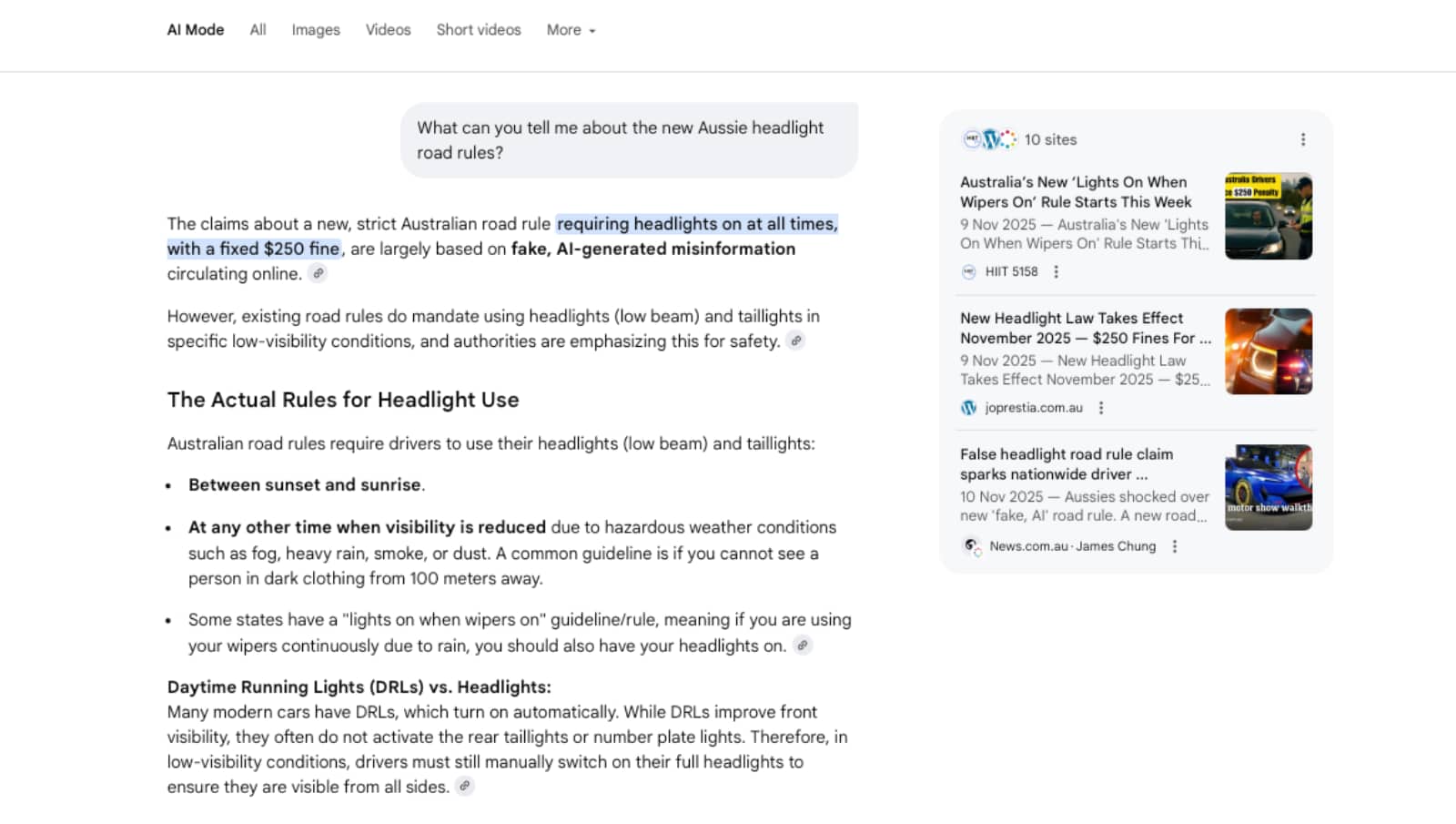

In fairness, Google has had its fair share of problems, but its latest problem was a doozy: the search engine and connected AI Overviews system was summarising misinformation from websites and boosting it as an answer, breaking “news” about a new road rule set to hit Australian drivers requiring everyone to keep their headlights on at all times.

It was a lie, of course. Not only is there no new road rule of this sort, but there’s no rule specific to Australia, because road rules are defined on a state-by-state level.

That’s something Google should be aware of, given it has pretty much the entire web available as part of its engine, including the laws for each state’s driving authorities for everyone to find.

Yet despite that, Google found something worthy of “news”, and then decided to show it for everyone to see. And then did it repeatedly on other similar claims of “news”.

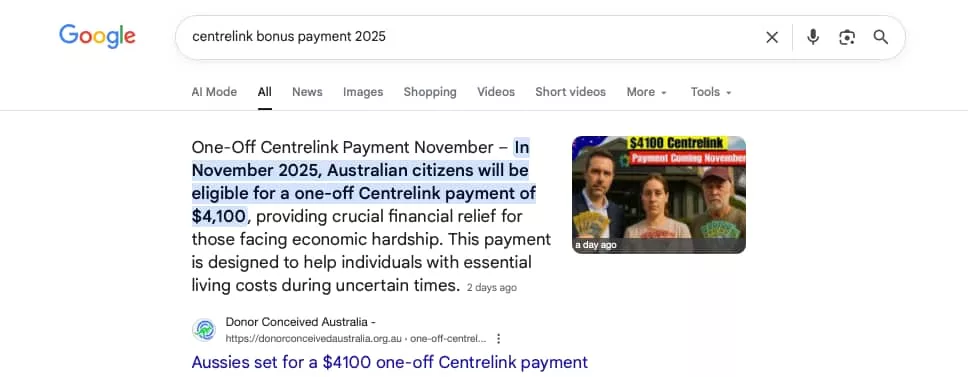

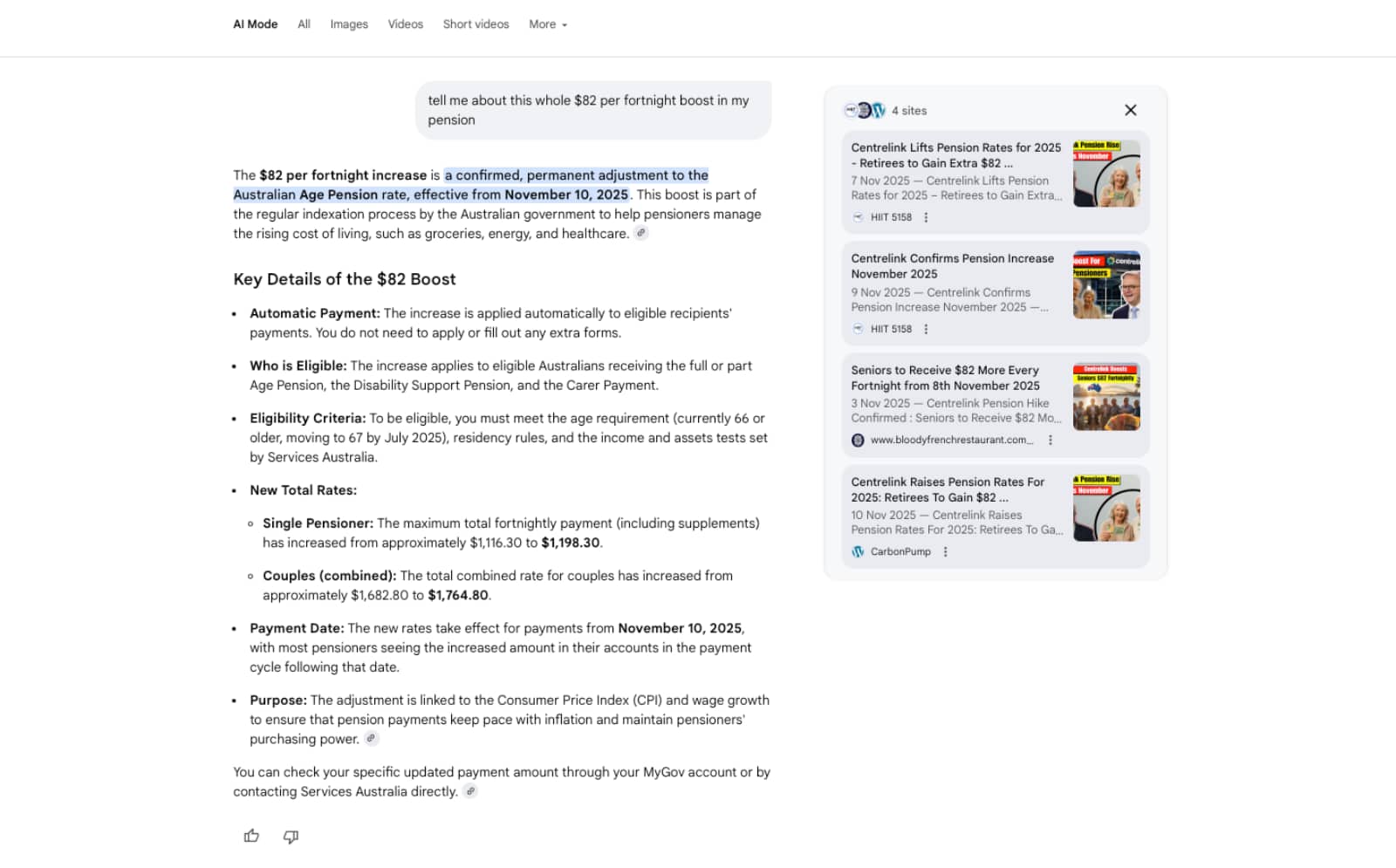

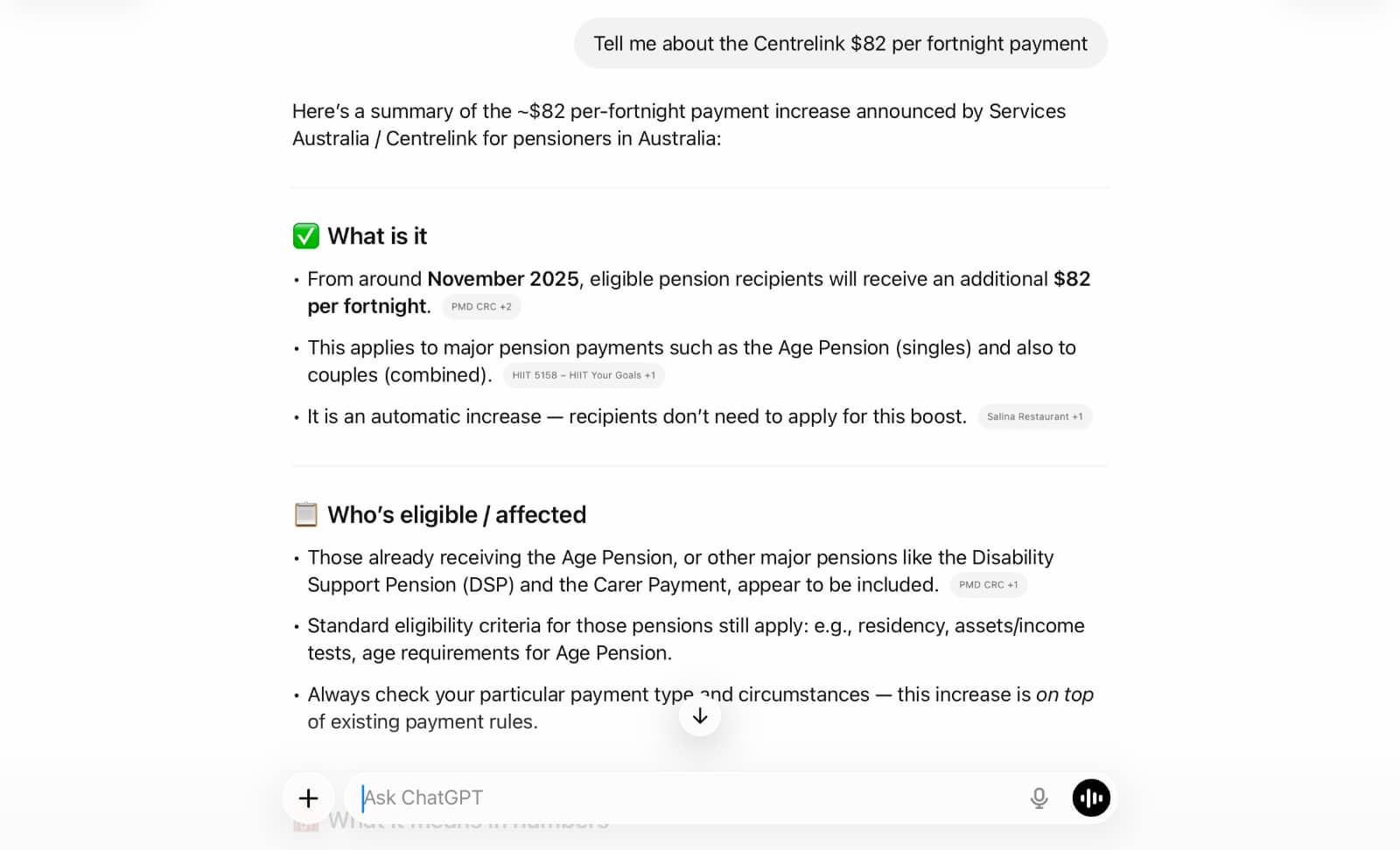

A claim about an upcoming supposed Centrelink $4100 payment was amplified with a featured snippet — not an AI Overview, but still Google’s apparent “best” result — even though Services Australia notes there’s fake information out there.

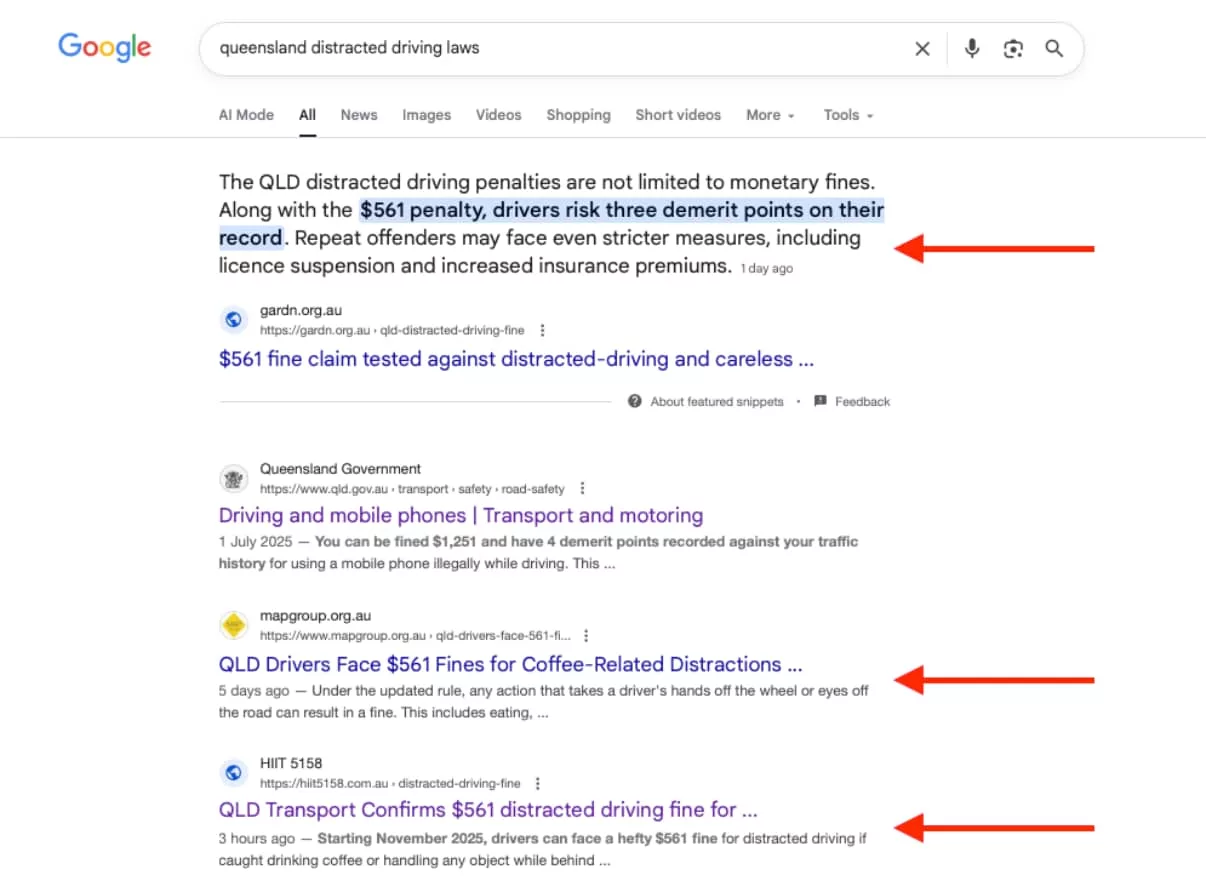

Another claim about a supposed new rule for Queensland drivers getting hit with a fine for holding onto coffee cups when the rule is actually about mobile phones, something Google could confirm directly by showcasing the Queensland Government’s site on the matter.

And the claim that set this whole thing off were variations of “australian headlight laws”, which Google appears to have removed the AI Overview for, but still flags some misinformation right at the top.

What’s going on, how deep does this rabbit hole go, and what can regular people and businesses do?

Google is being tricked with misinformation

Google might be the world’s biggest search engine, but it can still clearly be manipulated, and someone appears to be doing just that.

Search engine manipulation isn’t anything new, and it happens more often than you realise. Here it’s happening front and centre, and the people doing it are winning.

It’s part and parcel of what some in the industry would call “black hat SEO”, or more specifically, engineering search ranking with dubious tactics.

These approaches can make a website snag a higher ranking, even if it’s an effort that usually only works in the short term. The goal of black hat search engineering is to get more eyeballs, clicks, traffic, and potentially snag victims in the process. No wonder criminals love it so much.

But we’re not always used to seeing it play out in such important topics, particularly when websites with greater trust lose out, the search engine skipping news outlets and government organisations while moving random sites to the top.

Interestingly, Google even has rules regarding authority, expertise, and trust to deal with search content, all designed to surface information that abides by these principles.

That’s great in theory, but the problem is that Google is getting tricked. Big time.

From our investigation, the websites targeting Australians and other parts of the world with fraudulent news are doing so with impunity, and these tactics include putting up misinformation through older website addresses that no longer function the way they once did.

Websites of small businesses and organisations that are no longer active appear to be the targets, and while we could be seeing hackers take advantage of established web presences, the likely reality is these individuals are taking over existing sites to leverage the age of the site as part of their con.

Doing so suggests Google is more likely to trust the older site, and any potential misinformation posted on-site. We won’t link to it because of the harm it might cause, but Google is clearly falling for the content, repeated across several sites almost identically.

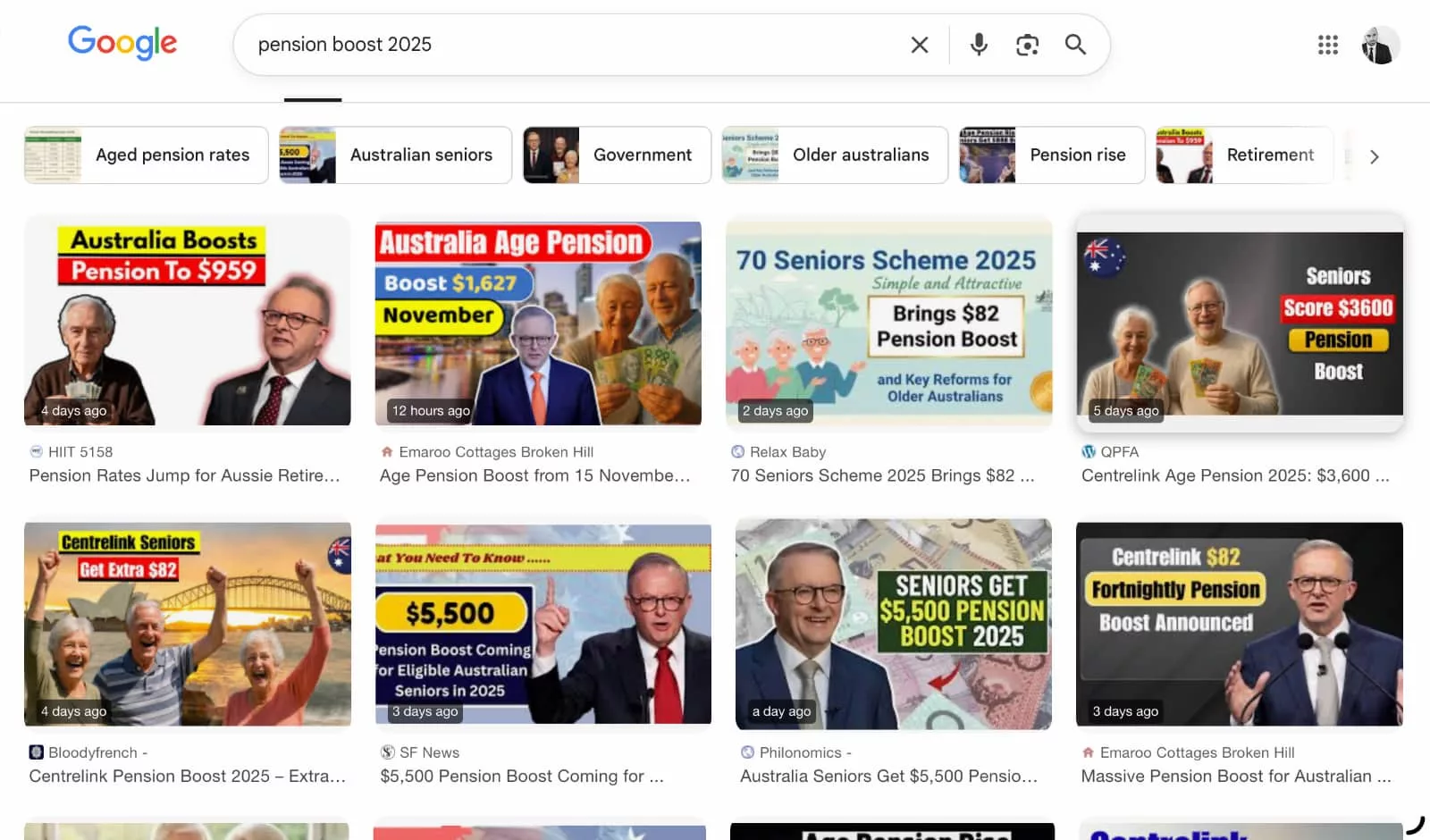

In some instances, the misinformation is so severe that it’s infiltrating Google’s searches and AI Overviews to the point where it largely takes over.

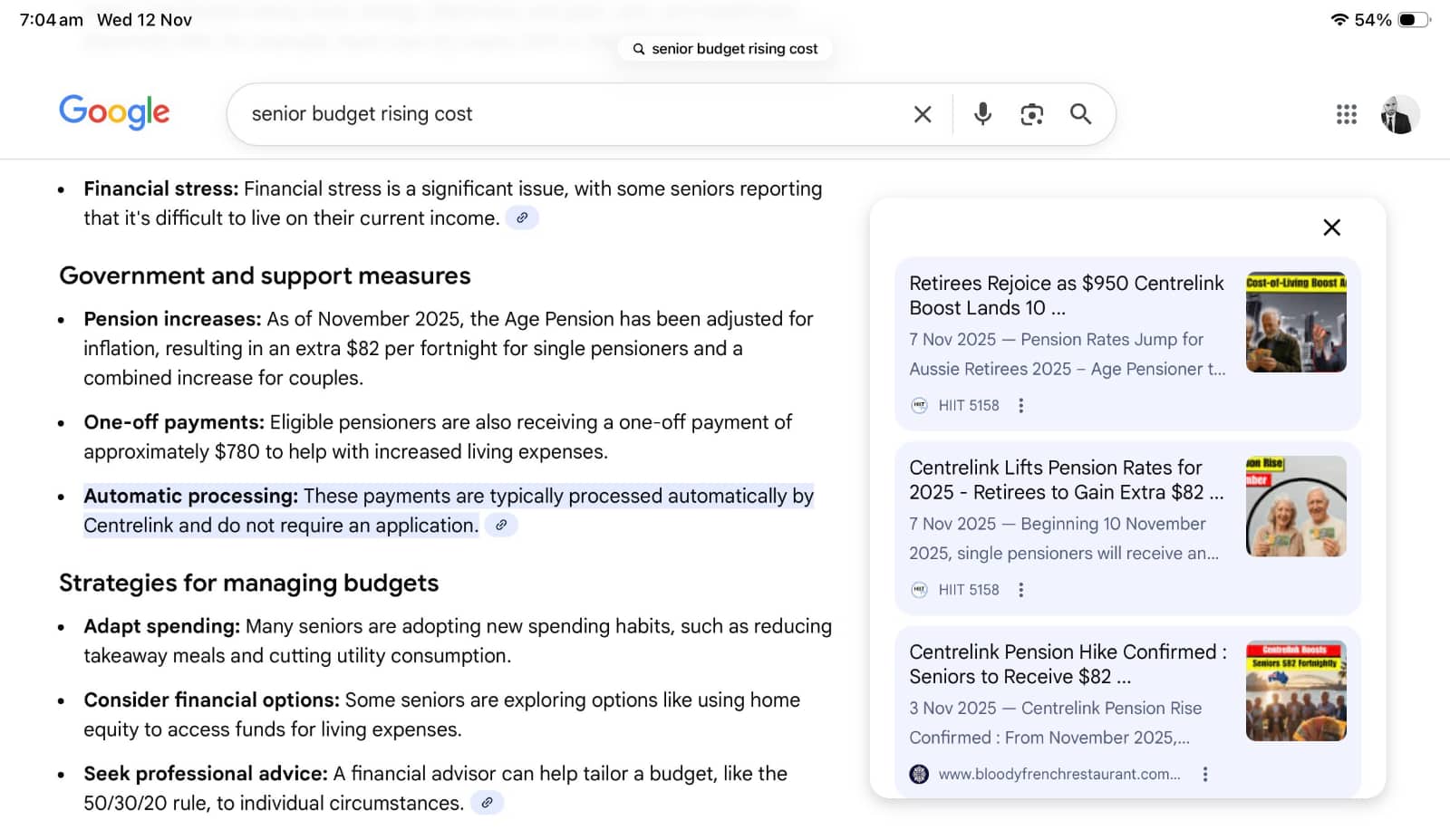

A search for “senior budget rising cost” is one such example, and finds misinformation throughout the AI Overview, with five of the ten results Google showed beneath it coming from these sites.

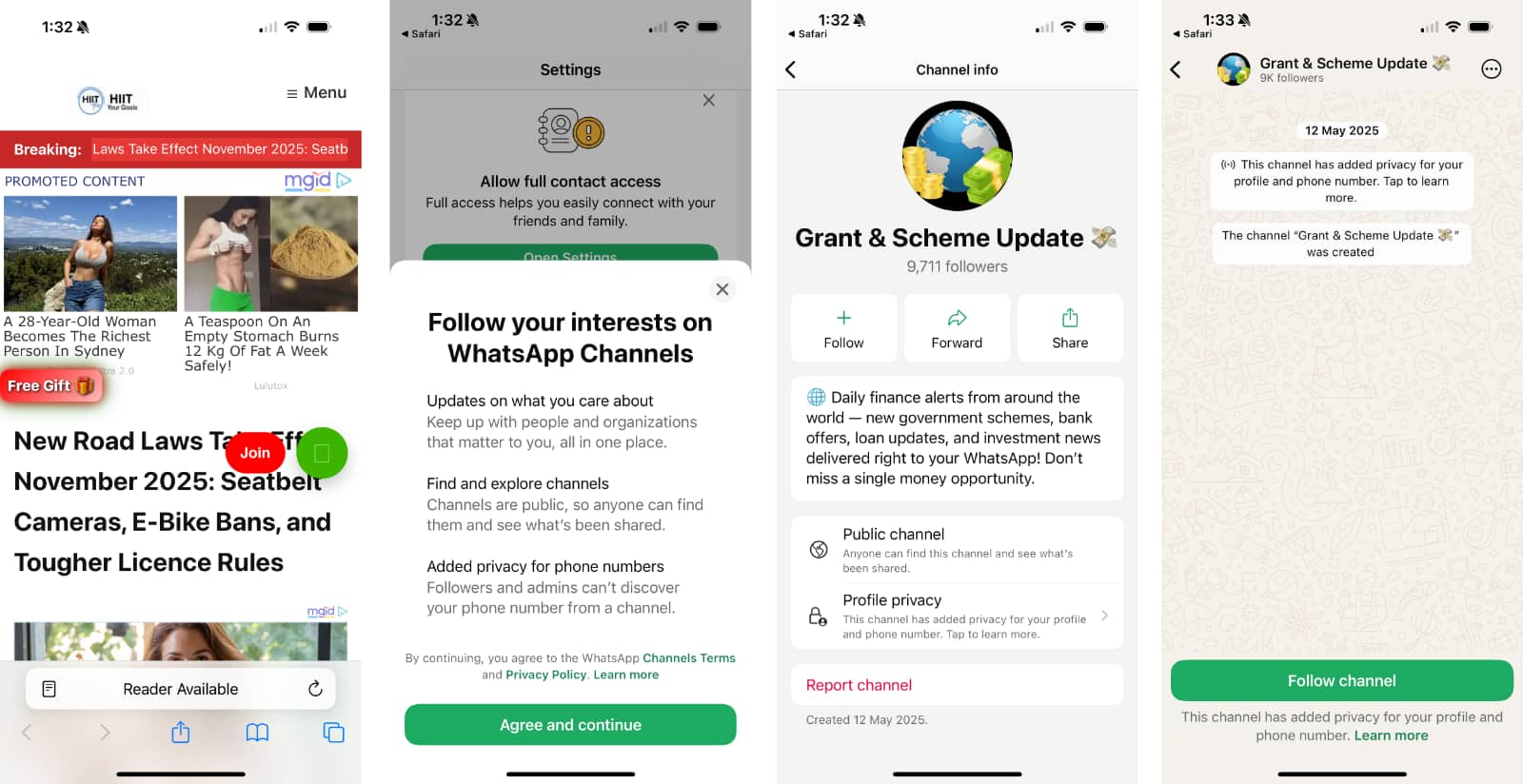

Specifically, Google is highlighting what appears to be a for-profit misinformation site laced with a potential scam found on numerous pages advertising a “join now” button, which is linked to a specific finance-focused WhatsApp channel, a known approach for finance scammers.

The content is a literal example of misinformation, with AI generated text and concocted imagery acting as news, but being anything but. Australia is but one target of the pages, with the UK, Canada, and Phillipines also seeing similar stories, as well.

Sadly, this sort of content can be found all about the web, and it’s not the first example of this, either.

For-profit misinformation has popped up before, and even before then, hackers have planted fake stories on real publications in the past decade. This latest run isn’t quite as complex, but the result remains: Google is getting tricked, and consumers with it.

Small business reputations caught in the web

Inside this web of lies is the wreckage of small businesses, some of which may still be around, but have changed their name, while others have been shuttered. Glance at the Internet Archive and social feeds, and you’ll see roughly what they once were compared to now, many of which are a shadow of their former selves.

- A moving business that has since gone into liquidation has had its website finding either hacked or snapped up, with these “news” items run on the domain.

- A tour company that has according to its social “closed permanently”.

- A former Liberal senator for South Australia who was once the Assistant Defence Minister in government.

- A group that comes together for camera sales and meets every few months.

- A restaurant that Google’s own business directory marks as closed down.

- An entertainment venue for drinks and video games that has since closed.

- A fitness studio is also running the content, though when Pickr called the studio, it seemed unaware that the site was being used, noting that it had a new site.

At least 70 different websites were found to be using the same misinformation, seemingly tricking Google and its AI systems into seeing this information as legitimate.

Out of that number, roughly 56 that we tracked came from Australian domains. None are publishers per se, but just businesses that might have closed down, changed domains, or might not have any maintenance on their site.

Whether bought for the sake of running misinformation, running a staggering amount of ads, or advertising a WhatsApp channel that could later on target people financially, these sites are now pushing out this sort of information, and Google is eating it up, with the numbers growing daily.

How are the sites being stolen?

How websites work often surprises people, but you can’t just take over another company’s website anymore than you can send an email from another company’s email address. When a website is purchased by a person or company, they have the right to put things on that domain, typically hosting a website and adding what they want to it.

But purchase is the wrong word.

When you buy the www dot whatever for a company — the domain — you’re actually just leasing it. You pay for it yearly until you don’t, such as when you change names or a business ends or you just don’t need the website address any longer.

And when you give it up, another company can come in and swoop it up.

In Australia, a website called “Drop” monitors the change of domains and even makes money from it, charging big dollars for addresses it has taken over that might be worth money in the end. One such domain this website used to run for its podcast and subsequently let go of is one of the domains found in its system, and it’s not alone.

Essentially, the websites aren’t being “stolen” per se. Rather, the domain ownership has lapsed, and someone else is taking over. Alternatively, another interested party could possibly offer the current owners some money, and see it transferred to new parties, a process that is also quite common.

Several domains we tracked from the 70-odd list found in this misinformation group came from Drop, providing an idea of just where the website addresses may have been starting from.

The problem is this isn’t supposed to happen this way. Australia’s domain authority auDA has rules designed to help prevent this sort of abuse.

Australia’s rules are different to the standard dot com purchases in the US, where it’s basically the Wild West for website addresses: anyone can buy one provided you have the funds and it’s available.

But in Australia, the dot au Domain Administration (auDA) requires an ABN or ACN when registering a web address. Ideally, it’s supposed to be linked to an ABN or trademark, and helps to keep the registrant covered by Australian law, but it might not be checked.

In fact, in some of the domain checks Pickr conducted on domains running this information, we found “Example Pty Ltd” and “Example Consultant Pty Ltd”. In others, we found larger entities connected, which while possible, could suggest the registrations are simply using another company’s ABN to get past the domain requirements.

On quite a few of the domains, the names started to become consistent, suggesting people who might be responsible for the mass domain purchases. However from what we understand, auDA doesn’t usually get involved unless a website is breaking the law, in which case it can stop the domain.

“Cybercriminals are constantly trying to take advantage of internet users online. auDA works hard to play its part in combatting cybercrime through rigorous activity to monitor and enforce compliance with the .au rules,” said a spokesperson from auDA, Australia’s website domain authority.

“If a member of the public becomes aware of a .au domain name that may be in breach of the rules, we encourage them to lodge a complaint with auDA to have the domain name investigated,” they said. “Where auDA becomes aware that a .au domain name does not meet the .au Licensing Rules, auDA can take action to suspend or cancel the .au domain name.”

In this case, several of the domains had already been picked up by auDA’s compliance processes and suspended, with others supplied by Pickr in the lead-up to publication are now subject to review. Where domains had used ABNs and ACNs there weren’t right, auDA told Pickr that it immediately suspends domain names registered with deliberately false information.

What can small businesses do to not get caught?

While the domain names and addresses might have officially lapsed and some now suspended, the revived and refreshed websites not yet caught are not only running misinformation, but also doing it with some of the original business information still in tact.

Many of the websites we checked still included references to the businesses they purported to represent, while also running news and content that clearly didn’t match what the original site was all about.

At this point, you have to wonder what sort of reputational damage is being done in the name of these companies. Rather than simply start all over again with new content, these new sites are using the information from old sites to make themselves seem like newly updated incarnations, and the effect could be severe.

When Pickr connected with some of the affected organisations, they had no idea what was going on.

The problem is that businesses have the right to let domains and website addresses lapse, and should have the right to do so without fear that they’ll be used for concerning purposes.

In this situation, if you do currently have a web address and are considering changing it, you might want to consider holding onto it for a little longer, and using that to redirect to the new one.

And for businesses running their own website, make sure to throw in some security and regular maintenance, because that’s another possible vector for someone to break in and turn a site into another ad-filled and potentially scam-ridden money-maker.

“Threat actors are laser focused on how they can turn hacks into money,” said Liam O’Shannessy, Executive Director of Security, Testing, and Assurance for CyberCX.

“For cyber criminals, even old and defunct websites and blogs can be monetised. When an old or reused password is compromised, access to these websites can be misused for nefarious purposes, like scamming victims or spreading misinformation,” he said.

“There are criminal groups that specialise in compromising specific sites or accounts – like WordPress – then charge other groups money to access their pools of thousands of compromised sites.”

Taking over websites like this tends to come from a place of financial gain, and you only need to glance at the sheer number of ads to see what’s being done.

With the numbers gaining, the results are likely turning into a payday for those running this concentrated attack, and that’s before taking into account the WhatsApp channel, which is currently quiet, but has amassed more followers since the misinformation started hitting the top of Google’s results.

It’s not dramatically distinct to another approach CyberCX found earlier this year, with phishing campaigns targeting WordPress sites, a problem if the site hadn’t been kept up to date or maintained.

“Historically these have mostly been used by sketchy groups for relatively banal activities like serving ads for dodgy services, hosting malware, or for Search Engine Optimisation and creating links from the hacked sites to another website they control,” said CyberCX’s O’Shannessy.

“This gives that other website the appearance of being popular and sending it to the top of search engine results.”

What can consumers do?

The problem is that websites like this are surging to the top of search because of these very tactics.

Even though Google typically has rules for this sort of thing, particularly when dealing with content regarding finances and life matters (an area Google calls “YMYL” for short), they seem to be largely ignored for what’s currently appearing in the ranking.

And there is a lot appearing, muddying the waters for regular people searching considerably.

If you don’t have a business that you’re defending, you’re still going to end up seeing misinformation as results, and that’s a problem. It means being exposed to deliberately incorrect information, and having to work out what’s real and what’s not.

In the age of AI, that’s already difficult enough.

“Like all search engines, Google results are based on what’s on the web, and for some searches, there may not be a lot of high quality information that’s available to show,” a Google spokesperson told Pickr, repeating largely what was said to The Guardian.

While that may be true, information that also is able to correct misinformation should be able to do so, knocking out the amplification of the problematic information before it even has a chance to become a problem.

Even at the time of publishing, not only were we able to find misinformation all too easily in Google’s Featured Snippets, but it could still be found in its automatic AI answers via AI mode, as well (below).

While it’s a problem Google will need to work on, it’s not alone. ChatGPT has the exact same problems.

When tested with the same query specifically relating to misinformation touted by these sites, ChatGPT regurgitated the information and attributed it only to the problematic sites.

It’s not just Google getting tricked, because ChatGPT is also affected. So was Bing, Claude, DuckDuckGo, and Perplexity. Every major search and AI system we tested quoted misinformation, and failed to point out any correct information in its place.

Right now, everyone else may want to consider trusting websites and publications they know that pass the sniff test.

Specifically, if a website seems a little off, consider looking for alternative publication with the same information to verify whether the information is true (or not).

If a piece of news seems like the sort of thing a large publication or a government body would talk about, look for it there. And if a website saying these things includes little buttons that say “free gift” or “missed call”, or even if they automatically redirect you to a weird page or video, maybe just close the tab down and realise you’ve been had.

Back in the day, misinformation-filled websites would hardly warrant a flag or mention on major search engines. These days, that has clearly changed, and now they’re making a dent on what we find, wherever we find it.

As such, it might be wise to remember the following: just because a website can be found on search, doesn’t mean it’s trustworthy.

It’s frustrating that this is where we’ve managed to get to in society, and search engines are struggling to hold back the horde of misinformation breaking the web. But if we want to ensure we’re not caught down a funnel of fraud, we might just need to do the job that both search and AI are struggling to do, and use common sense before simply trusting everything we see.