On December 10, Australia wakes up differently. The world wakes up a little differently, too, as a country eyes what life is like when you block a population from accessing something they’ve always technically been able to use.

The social media ban for under 16s is here, much to the chagrin of a population likely feeling unheard, and keen to challenge it in the courts.

While social media services have never been focused entirely on kids and teens, kids and teens have been able to use them, the recommended age of 13 and higher merely just an obstacle to them beginning an online life.

Parental connections existed if parents enforced them, but by and large, anyone under the age of 16 was using social media largely unchecked, and that can be a problem.

So the government is stepping in, with regulation that feels rushed as to how it was approached, and even to a degree in how it has been developed.

A year is a short amount of time to go from idea to action, and the result may be a concept that ends up providing protection while limiting independence.

What is happening, and is this new regulation really a law you have to follow?

Is the social media age regulation an actual law?

Officially enacted across Australia, the Social Media Minimum Age system also known more easily as the “SMMA” is technically a law, with amendments to the Online Safety Act of 2021.

But it’s also a law that carries no penalties for kids or parents. Rather, it’s a law more specifically targeting social media platforms, meaning that the people using the platforms won’t face criminal penalties, just those operating them.

We probably don’t need to summarise what’s going on, but the law requires social media platforms to take “reasonable steps” to prevent anyone in Australia under the age of 16 years from having an account, what the government believes is the minimum age to apply the rules to.

The regulation goes further to say that no Australian must be compelled to use government ID to prove their age, and that platforms have to offer other solutions, but that privacy protections also need to be in place to destroy required data, as well.

Part of the reason for the suggestion of the age 16 has to do with vulnerability, and how online life and social media can affect growing kids and teens. In short, the idea that they may not be ready for social until they’re older, at which point any account they previously had before they turned 16 would be made available to them again if they wanted it.

What services are officially banned for under 16s?

From December 10, that’s the lay of the land, and several services have to comply immediately, including:

- Kick

- Snapchat

- Threads

- TikTok

- Twitch

- X, and

- YouTube

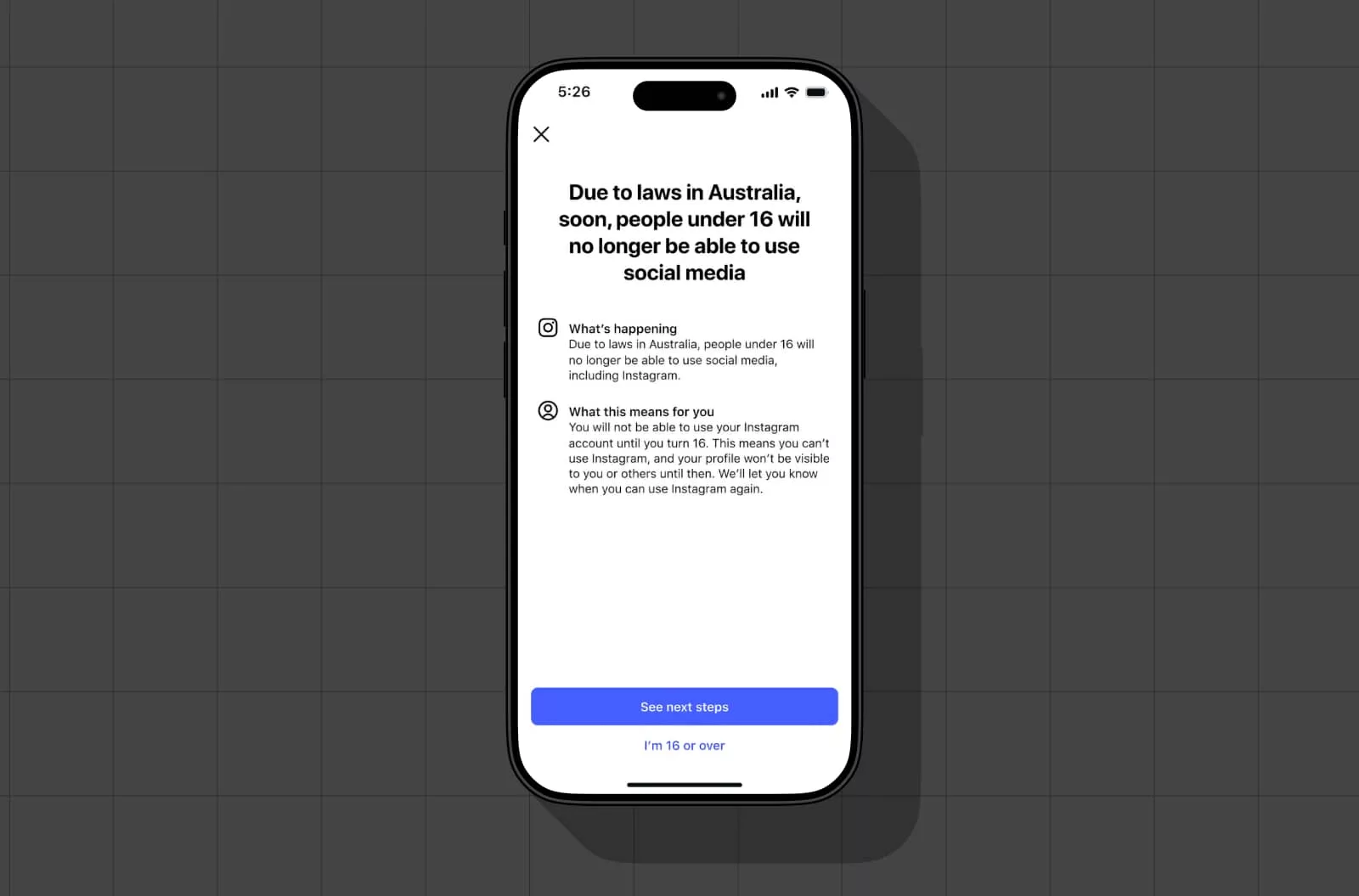

Some of these services were proactive in how they rolled out, but others left it to the last minute.

While Meta was early on its approaches, Reddit left it to the eve of the ban before announcing what they would do. Even X has complied, hardly a surprise given the risk of major fines and the fact that it also offers advice age regulation in other countries, as well.

What isn’t blocked?

Not every service has been called out and is blocked for under 16s, with the likes of Mastodon, Lemon8, Yope, and more not under the watchful eyes of the Australian government, at least not yet. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these apps are pushing their way to the top of the App Store charts on iPhone, a clear sign that kids and teens are looking for solutions.

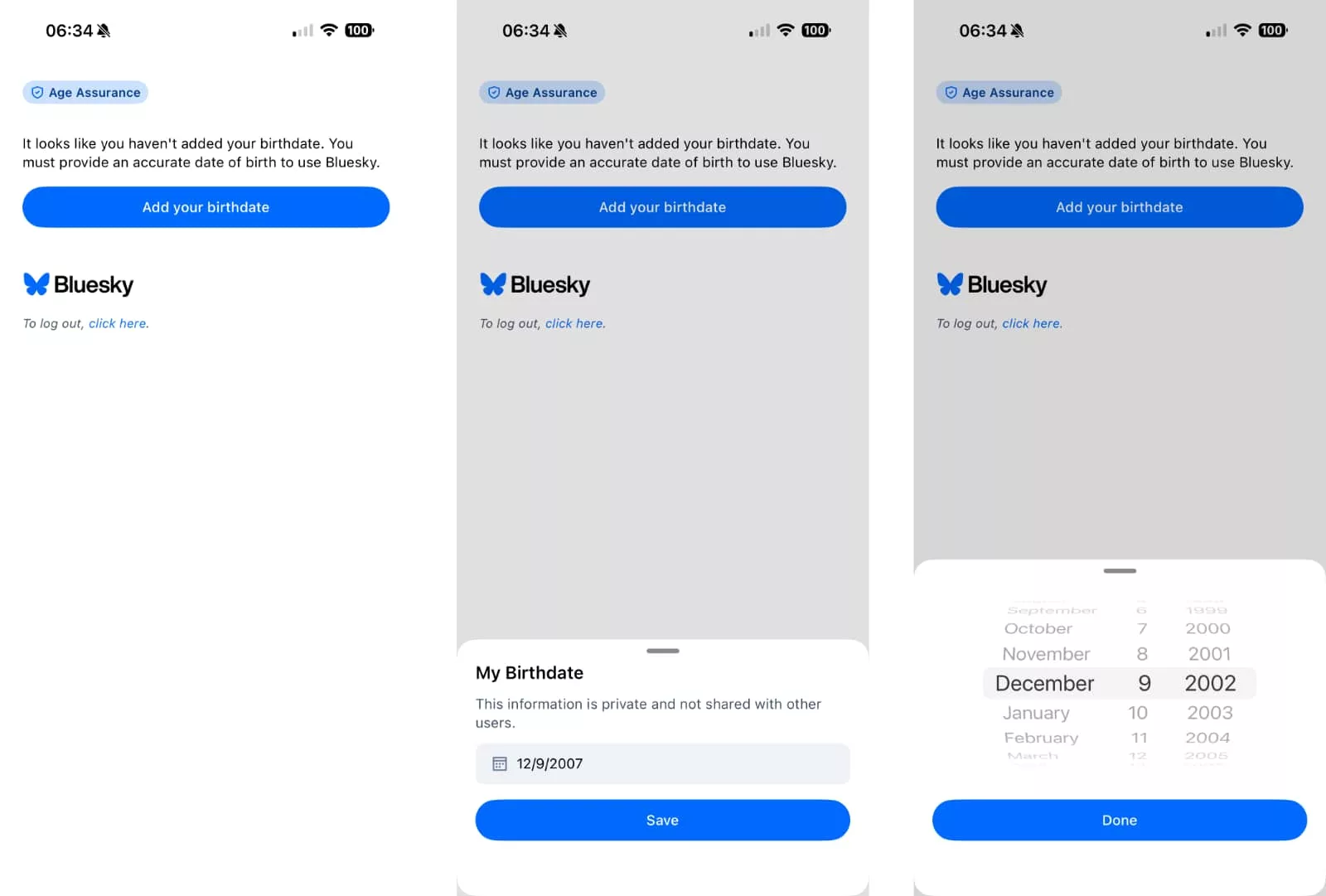

Clear X competitor Bluesky technically isn’t required to age verify, either, but on the morning the social media ban kicked off, it too added a birthdate verifier, a field which started just early enough in birth years, but essentially relies on trust.

While other services are being asked to classify themselves, the reality is that only the initial few are affected.

In fact, the government has said the following platforms will not be age limited when the services goes into effect:

- Discord

- Github

- Lego Play

- Messenger (Facebook Messenger)

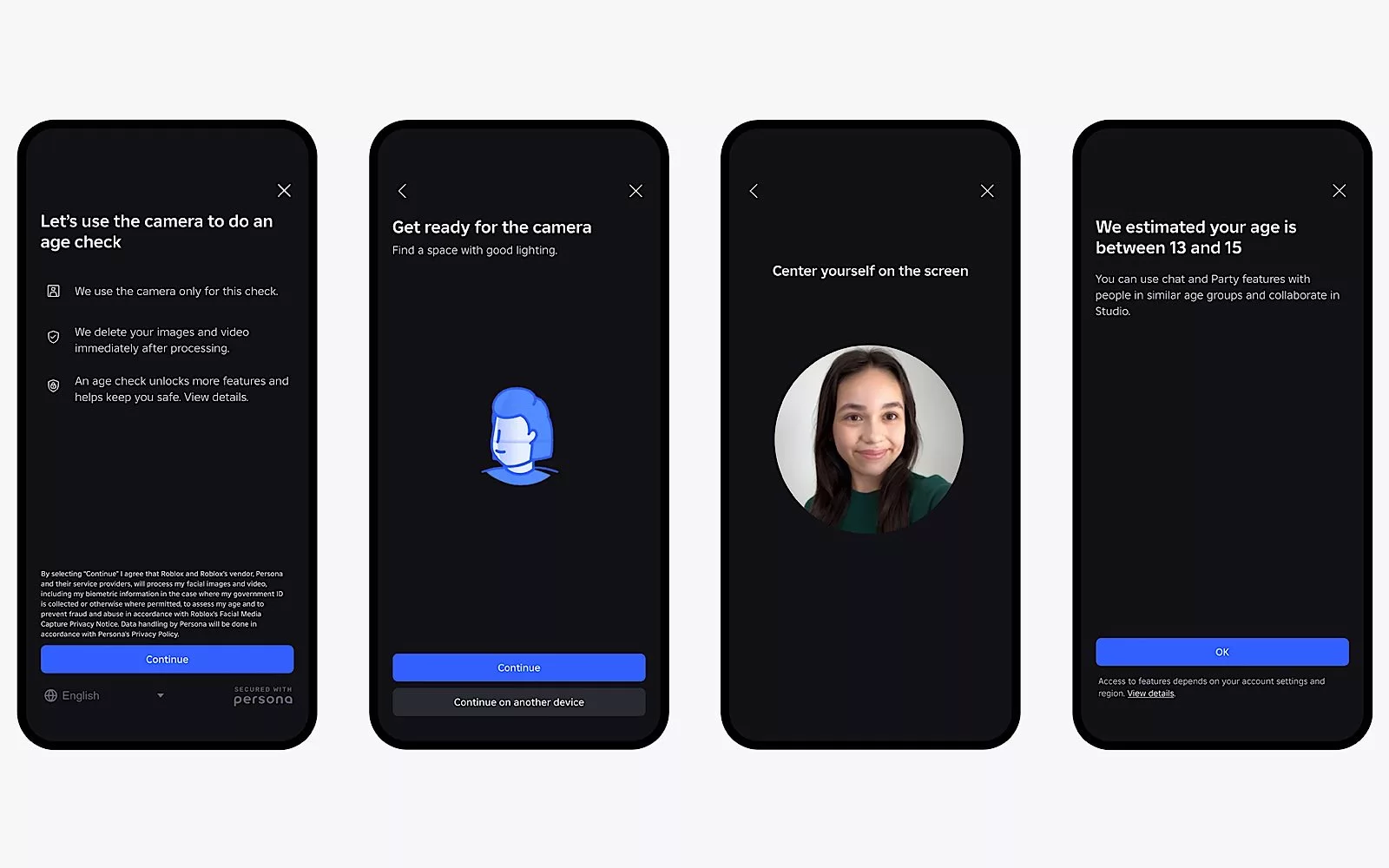

- Roblox

- Steam

- YouTube Kids

There are likely others, with smaller services not included, and of course websites that act as forums are also not likely affected, either.

Will the government apply the ban to other social platforms?

But some services sure proactively applying the law ahead of any announcement, likely in case they get targeted directly. Remember that if a social media company is called out directly, it risks infractions attracting heavy penalties, so the government is giving services a reason to fall in line, so to speak.

It’s also highly possible that some of the previous aforementioned unaffected services will be asked to apply age restrictions later on, as well.

Roblox took the step of being one of the first to apply age verification, even ahead of other larger entities, and it isn’t actually included.

By comparison, a service like Mastodon could be more difficult to adhere to any age verification law due to the decentralised nature of its service, and how it relies on servers and respective server rules, rather than simply being a service that runs from one specific place.

But that doesn’t mean it and other unaffected services will be safe. Previously, the eSafety Commission has sent guidance to Lemon8 and Yope putting them on notice as potential targets of the law.

What does it mean for accounts under 16?

Regardless of which service follows the law, anyone under the age of 16 with their age verified as such will start to see accounts locked or suspended from here.

It means if you have an Instagram or TikTok account, and you’re verified as under the age of 16, not only is your account now suspended, but the content won’t be viewable by anyone else.

Any account on a platform where the verified age is below 16 will essentially be suspended and locked. While its data can likely be exported, the account in many ways acts like a bit of a time capsule, and won’t be eligible for a return and re-activation until the owner turns 16.

Could the law do some good?

While not everyone may agree with the regulation, there’s little doubt it could do some good. Some young people are even looking forward to it.

The President of the Royal Australian College of GPs, Dr Michael Wright, welcomed the changes, noting that “adolescents are experiencing significantly higher rates of anxiety, alongside increased incidents of bullying”, pointing the finger to social media.

“We know that children and young people are spending extensive time on social media, and this is restricting their sleep and impacting their overall wellbeing,” said Dr Wright.

“While many parents are deeply concerned about the effects of social media, there is often reluctance among children themselves to reduce their usage. This highlights the challenge families face in managing online engagement.”

Research has linked social media to mental health in young people, with research from Headspace, ReachOut, the University of Queensland, and Yale’s School of Medicine, to name a few.

You don’t need to do much searching online to find an impact to mental health cause by social media. It’s pretty clear social media regulation for kids and teens could have some positive effects.

Does the law have the potential to harm?

The problem is it could also do harm, as well.

Kids in rural areas may find themselves more isolated than ever, and under 16s who find solace in connecting with others online may find themselves disadvantaged. They may even find themselves driven to lie about their age to stay online.

Parental controls for YouTube will no longer work, either, due to how YouTube no longer allows accounts for anyone under the age of 16, and so the rules that once governed family-connected accounts will no longer be in place. That could make surfing YouTube in a logged-out capacity worse for young people, what will likely be an unintended side effect for the government’s regulation.

It could also affect parents and kids negatively by encouraging one to look for ways to stay online, and discourage kids from talking to their parents. That’s an important part of this whole process, and perhaps one of the unintended side effects of what the ban is doing.

If anything, parents and kids need to talk about online and social, enforcing the bonds of trust and respect each should show each other.

Do parents and kids have to follow the social media age law?

But this might be one law that you mightn’t have to actually follow, with the government initially declaring that parents and kids wouldn’t be penalised for infractions of, and confirming ahead of the ban:

…there are no penalties for under-16s who manage to create or keep an account on an age-restricted social media platform, or for their parents or carers.

In short, kids can try to use social without risk of anyone fining or penalising them, and the same is true with parents who wish their kids could keep using social media.

The problem is that social media companies will need to take steps in order to prevent those actions.

So it becomes a bit of a catch 22: you can have the account, but the service won’t let you run the account if you run it for your age.

That could possibly lead kids and parents down the path of deception, and it unfortunately is what it is. Ultimately, parents intending to support their kids will need to find ways to do so, to listen and be there for them, and look for ways to help plan and deal with the ban where they can.

It could become quite normal for kids who wish to stay online to get their parent’s permission to use their face or age, and stay online that way. It won’t be an account truly respective of their age and name, but it should allow both to skirt the rules, even if it doesn’t really solve the problem the law was developed to deal with.

And many kids will be doing just that, with over 10,000 noting in an ABC survey that they plan to keep using social media when the ban comes into play, with almost as many expecting that the regulation simply won’t work.

There could have been a better way of making the social media age requirements better for everyone, kids included.

Is this the right approach?

As a journalist and a parent, I’ve made no secret of saying what I think the government should have done, noting that the process has been rushed and essentially tramples on both a parent’s rights and the rights of their kids, growing adults who are looking to find their own way through life.

It is therefore altogether surprising that the government hasn’t embraced the idea of parental-linked accounts for under-age social and essentially forced parents to take part in the internet-connected learnings of their children.

That alone could have leaned into the very parental controls that existed, and forced social media entities to not only join the dots between youth and guardianship, but also forced social media entities to do a better job in policing the problems of social media.

Further, parental-linked accounts would have given parents a way to talk to their kids about social media, and allow them to learn together, rather than bury collective heads in the sand and say “you’ll be right” when you turn 16.

The problem is this: age doesn’t necessarily denote readiness, and adults can be misled by the problems of social just as easily as kids.

Anyone can fall victim to scams and social engineering and algorithmic manipulation and do on, and it’s foolish and flawed to say it is just a problem of youth. You only have to look at the severe losses accounted by adults falling for scams to see that it’s not just an age problem. It’s an education problem.

I agree that social media needs regulation, particularly in how it works with younger minds, raising and shaping them.

But regulation is not prohibition. They are not the same. They may be used in similar ways, but prohibition typically exposes the problem and makes it taboo, shining a light on it and giving the disenfranchised a reason to circumvent it.

So if the government wants to address improving the problems social media brings to a potentially more vulnerable crowd like kids and teens, it needs to ensure it is being taught how to deal with it, and that means education.

What needs to happen: education

Ahead of the ban, the government has said it will offer educational resources on its eSafety website, but let’s be real. Whoever actually reads anything supposedly “educational” from the government, and since when is the government’s understanding of technology ever trusted as being up to date or reliable?

If the government is serious about social media education, it should introduce programs into schools and develop formalised approaches to teaching about social media, about scam awareness, and involving parents in the system.

Education is almost always the answer to ensuring better growth and progress, and simply pointing to government resources on an evolving problem hardly fixes anything.

What’s next?

We’re in uncharted territory here, as Australia tries something never seen around the world.

Australia’s teens and kids under the age of 16 are waking up to a world where the internet no longer accepts them the same way it did a year ago, and that’s an interesting situation.

It’s potentially fraught with problems, even for parents, as the school year ends and families are treated to several weeks of holidays until February 2026. While one positive could see kids encouraged to go outside and play with their friends, the simple reality is life isn’t typically like that.

The Prime Minister may wax lyrically about wanting kids to “grow up playing outside with their friends, on the footy field, in the swimming pool” and so on, the reality is many may not connect that way. Some kids and teens find connection on the internet, through social media, and this may prevent them from doing that.

But it’s all very much early days, and we won’t know what’s next until Australia has experienced some of it.

And the world is watching, because it’s not just Australia eyeing the effects of social media on the youth. It’s seemingly everyone else, too.